There were once three railway stations in Salisbury: Salisbury Milford opened in 1847 as a terminus of the London and South Western Railway line running from Bishopstoke (where a connection could be made to Southampton or London); Salisbury Fisherton (GWR) opened in 1856 as a terminus of the Great Western Railway line running from Bristol through Westbury and Warminster; Salisbury Fisherton (LSWR) opened in 1859 as a stop on the Gillingham to Salisbury section of the London and South Western Railway Salisbury to Yeovil line. A short branch line was opened in 1859 to serve the city’s Market House (now Salisbury Library) and remained open until 1964.

Milford Station was closed to passengers in 1859, when a loop was built connecting the LSWR line through to the company’s new station at Fisherton, although Milford remained open to goods traffic until 1967. The Fisherton GWR terminus was closed to passengers in 1932 and to goods in 1991, by which time it had long become absorbed into the complex around the modern day Salisbury station, centred on the original Fisherton LSWR site and buildings.

The London and South Western Railway opened at Fisherton in 1859

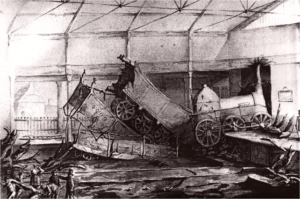

On 6 October 1856, just four months after the Salisbury Terminus had opened, a loaded GWR livestock train – pulled from Bristol by two engines – passed through Wilton station, to the west of Salisbury, at a rapid pace that increased to the extent that when the train reached the terminus it simply kept going and carried everything in its path along with it.

The four sunken posts against which the buffers of the engine came in contact were snapped off and the floors and joists of the platform, as well as the walls of the ladies’ waiting room, were cut through cleanly as though, according to the Salisbury and Winchester Journal, ‘it were the work of carpenters and masons’.

The outer wall of the station was knocked through and the first engine finished up parallel with the walls of the street outside. The rearmost part of this first engine was now resting on the foremost part of the second, which because of the weight was embedded in the ground. The impact had caused the tender of the second engine and the first carriage to be tipped up, so that both were in a perpendicular position. The second carriage had also been tipped up, with the third entirely thrown over on to the fourth.

The stoker of the first engine had jumped off on to the platform and struck his head, but otherwise was uninjured. The driver, Mays, had however kept to his post and been carried through to the street unhurt.

The disaster which happened to the livestock train on 6 October 1856

The scene within the station resembled a chaotic slaughterhouse as the station was thrown into ‘panic stricken…dismay, confusion, perplexity and darkness’. The gas supply was extinguished in case of fire, so the only light available was from a few candles and dark lanterns – the crowd that had assembled on the platform were stumbling into one another. The foremost engine was now emitting large clouds of steam, filling the station and reducing visibility further.

A fire did indeed break out, caused by the timber of the floors being ignited by the fire from the engine. A hose was immediately attached to the hydrants and water thrown from buckets to extinguish the flames – without this the station would probably have burnt to the ground.

Nothing had yet been done to remove the animals, and the bodies of the two dead humans had not been discovered. At about half past ten, sheep began to be removed. A few were alive, but many more were badly mutilated. The majority were crushed to death, whilst some had legs sliced off or broken, and others’ entrails were protruding from their torn bodies. Local butchers Messrs Judd and Dowding, were called to slaughter the injured animals.

The bodies of the engineer and stoker were found crushed between the tender and the firebox of the second engine, with only the hand of the former being visible from the outside. The Inquiry into the crash concluded that ‘the distance between Wylye and Salisbury was travelled over at excessive speed for a train of this description [and] that this speed was continued until the train had arrived so near to Salisbury that the head guard became alarmed, applied his break and kept it on’.

Almost fifty years later, in the early hours of Sunday 1 July 1906, the sound of screeching metal and the screams of the injured and dying were again heard emanating from a Salisbury station, as a boat train travelling from Plymouth to Waterloo ploughed into an early morning goods train stopped on Fisherton Street Bridge at the LSWR station.

The rail disaster left 28 people dead and many more injured, and the noise of the crash reverberated across the city. Doctors were fetched and people flocked to help the rescue operation. ‘As day dawned on Sunday’, noted the Salisbury Times, ‘Salisbury was the scene of an unparalleled catastrophe’.

The scene at the terrible railway disaster which happened Sunday 1 July 1906 © The Frogg Moody Collection

43 passengers, mostly Americans, had disembarked from the transatlantic liner SS New York and boarded the Ocean Express at Plymouth, crewed by the driver William Robins, fireman Arthur Gadd, a guard, two waiters and a ticket collector. It was common practice for the more affluent transatlantic passengers to take the boat train from Plymouth (the first point of landfall in Britain) directly to London, thus gaining a day over those who sailed on to Southampton and Portsmouth and made the journey to the capital from there.

The cause of the crash remains something of a mystery, with the Inquiry being inconclusive and opinions advanced in subsequent years being no more than theories. As the boat train sped through Salisbury station at around 2am, it was travelling at such high speed that it left the rails immediately after passing through the sharp curve at the eastern end of the platforms, careered along on its side for about 100 yards, wrecked the rear wagons of the London to Yeovil milk train and then smashed into a goods train standing at the station.

The mangled remains on the boat train express, Salisbury Station, 1906 © The Frogg Moody collection

Driver Robins and Fireman Gadd died instantly and 24 of the boat train passengers were lost. The guard of the milk train and the fireman aboard the goods train were also killed. The station’s refreshment room was used as a first aid station, whilst the ladies’ waiting room on platform four was used as a temporary morgue – it was here that the firm of Kenyon’s (who were just branching out into disaster management) were employed to carry out a mass embalming of the victims.

A Mr Dacombe, the head of the firm of John Beeston & Co in Southampton, was contacted to embalm the majority of the victims. In order to manage the large number of victims involved he sought the assistance of Herbert and Harold Kenyon. Together with their staff member Harry Woolcott and funeral director/embalmer James Goulborn, they travelled to Salisbury.

After the coroner and chief constables had concluded their initial investigation into the accident, the embalming commenced at 1pm on Monday 2 July and continued until 5pm the following day – seventeen bodies were embalmed in total. Many of the victims had been severely mutilated and the situation was not improved by the extremely hot weather. The embalming was achieved through arterial injection and hypodermic treatment.

On Wednesday 17 July, Herbert Kenyon accompanied five of the bodies on the Cunard steam ship Carmania from Liverpool, arriving in New York arriving on 24 July. On arrival the bodies were examined and reported to be in a good state of preservation.

The book by Jeremy (Frogg) Moody & George Fleming.

Witten for the centenary of the Salisbury Train Disaster.

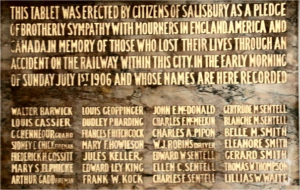

A memorial plaque can be seen in Salisbury Cathedral charting the people who lost their lives in the Salisbury Train Disaster of 1906 © The Frogg Moody collection