The New Fisherton Gaol

THE NEW FISHERTON GAOL – By Frogg Moody & Richard Nash

In 1808 it was decided that the old county gaol, near Fisherton Bridge, was unhealthy and at risk of flooding because of its close proximity to the River Avon, and it was decided that it should be closed. A site was chosen for a new gaol between Turnpike Lane (now St Paul’s Road) and the southern end of Devizes Road. At the time the later intervening Sidney Street and York Road had not been built and the area – nowadays dominated by the St Paul’s roundabout – was very much at the edge of town.

The Old Salisbury Prison near Fisherton Bridge.

Deemed unhealthy and dangerous to prisoners.

Work started on the new gaol in 1818 and it was first occupied in August 1822. The building work – carried out by Salisbury contractor John Peniston under the guidance of Mr T Hopper, architect – cost a total of £40,000 and every one of the bricks used was a ‘Fisherton’ – made on the spot from the clay that was dug out.

The new gaol was hailed as a great advance. The Salisbury and Winchester Journal commented that: ‘the general intercourse of prisoners, whereby the more abandoned are able to instruct the youth just launched into vice, in every species of depravation, is an evil which has been long felt. Our gaols have hitherto tended rather to confirm the prisoner in the habits of wickedness than to amend his morals. The present plan will unite the desired purpose of a reformatory with a place of confinement; every prisoner will be compelled to spend his hours in solitude; personal access of any but his keeper will no longer be suffered, and his diet must be of the ‘simplest kind, bread and water…’ The female prisoners are to be divided from the men and to be treated in like manner’.

The front elevation of the new Fisherton Gaol.

The gaol contained 96 cells with seven courtyards, including two for female prisoners. At the centre were the Governor’s and Matron’s quarters, a chapel and an enclosure for female debtors. The average occupancy was approximately round two-thirds of the overall number, with the number of committals usually fluctuating between 300 and 400 per year. A large percentage of the inmates were being remanded in custody, pending the six monthly Assizes.

The gate house was on the Devizes Road. Behind this was the Governor’s house, to each side of which were rows of dank below ground-level cells. These passed under what is now York Road on one side and half way to St Paul’s Road on the other. A similar row of cells was constructed behind the house and behind this was the Chapel.

Although the use of the gaol ceased in 1870 and much of the original structure was demolished in 1875, it was reported in the Salisbury Journal that the cells were damp, cramped – around eight feet by six feet – and with a brick vaulted roof barely six feet high.

Damp cell conditions faced the prisoners in Fisherton Gaol

The vaulted passageway was twice the width of the cells themselves. Access to each cell was through a small opening and, except perhaps for that gleaned from candles in the passage, the inmates would only have seen light when allowed into the yard for exercising. There was no evidence of any provision for heating. The debtors’ accommodation appeared to have been a single large open room. The old chapel remained in good repair – including the gallery probably used by priests to address the wretched congregation below.

A total of 71 executions took place at Fisherton between 1801 and 1850 – twelve of which were in the first year of that period. In many of the latter years there were no executions here at all – the last execution was in 1855. The condemned man was William Wright, who had been found guilty of the murder of Ann Collins at Lydiard Tregoze, near Swindon.

The last hanging at Fisherton Gaol was in 1855

The scaffold was erected early on a Tuesday morning and shortly before 11.00am the chaplain met with Wright in the prison chapel and urged him to use his last few moments wisely. The Holy Sacrament was then administered, and at 11.40 the murderer, accompanied by the under-sheriff and others proceeded to the gallows whilst the chaplain read the burial service.

Wright appeared deeply affected, sobbed violently and prayed earnestly. He took his leave of the governor and shook hands with the chaplain and the under-sheriff, before Calcraft, the executioner, proceeded to pinion him. Wright had expressed a wish to address the crowd, but now declined to do so. The procession ascended the steps to the scaffold. The condemned’s firmness held as he moved beneath the beam, the rope was placed round his neck and adjusted, and the cap drawn over his eyes.

The chaplain proceeded with his solemn service and at a given signal the bolt was drawn, and the unfortunate man was launched into eternity. Wright’s death was almost instantaneous and his fall from ‘The Drop’ caused a wound inflicted at the time of the murder to break out afresh, serving only to increase the horror of the spectacle.

In a 1919 Salisbury Journal article, a Mr Harding – ‘possibly the oldest resident in Fisherton’ recalled how as a boy he would be woken during the night by the noise of workmen erecting the gallows. He also spoke of the ceremony of these occasions – the procession from the gaol, the adjusting of the rope around the neck, the black hood, the reading of the burial service…the drawing of the bolt…

Executions were certainly a big draw – there was an estimated crowd of 15,000 at the hanging of Robert Watkins for murder in 1819, and a not quite so impressive 10,000 for that of George Maslen – hanged for attempted murder in 1838. Whilst it had risen to more than 11,000 by the latter date, at the time of the earlier, larger event the combined population of Salisbury and Fisherton Anger was a little over 9,000.

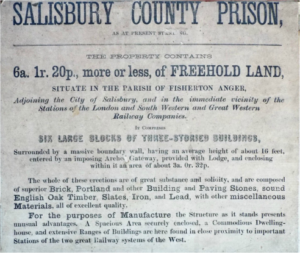

In 1866 a Royal Commission recommended the abolition of public executions and William Wright’s hanging proved to be the last in Salisbury – public or otherwise. Fisherton gaol closed in 1870 and the six acre site was later put up for sale. It was purchased in 1875 by Thomas Leach, a grocer who owned a shop in the Market Place, and Thomas Scammell, who had a business in Fisherton Street.

Salisbury County Prison, Fisherton, sale advert

© Frogg Moody Collection

Most of the buildings were demolished, but not before the site was opened for a public viewing on 1 July 1875. Nearly 2,000 curious citizens paid a total of £19 8s 10d (which was donated to the St Paul’s Church Enlargement Fund) for the privilege of inspecting the premises and listening to gospel addresses in the garden and a sermon in the chapel.

Following some demolition works the gaol building was renamed Radnor House and became a school for girls, operated by the Misses Harding where ‘a limited number of young ladies’ were educated at a cost of thirty five to forty five guineas per annum. The prospectus promised that each pupil would have a bed and advised they ‘should bring two forks, a dessert spoon and tea spoon, four dinner napkins and six towels’.

Mr E O Harding, a relative of the school proprietors, recalled how evidence remained of the somewhat less luxurious lifestyle of former occupants: ‘An uncle used to take me down to see the cells and used to scare the life out of me. At that time there were still marks on the ceilings of the cells where the prisoners had used candle smoke to make drawings. There was a moon and a sun among other things and I can only think they had to do something to do with their misery’.

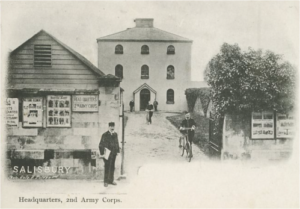

By 1905, St Paul’s Road, York Road, Sidney Street, George Street and Meadow Road had been built across parts of the site. Radnor House was by now owned by Dr Corbin Finch and leased to the War Department for use as an office for HQ Southern Command. In 1913 the remainder of the gaol grounds were also leased to the War Department by a Mrs Baskin. Huts were built on the site in 1914 and in May 1922 the freehold of the site passed from Mrs Baskin to the War Department.

Radnor House, Fisherton, leased to the War Department by Dr Corbin Finch

© Frogg Moody collection

In May 1940 the site was found to be too cramped and HQ Southern Command relocated to Wilton House. However, some ancillary services remained at Radnor House into the 1950s and, during World War Two, Salisbury’s No 1 Auxiliary Fire Station was set up at a former Wall’s ice cream depot in Devizes Road, on the site of part of the old gaol grounds.

The entire site was finally cleared in 1969 in preparation for the construction of Salisbury’s relief road, now known as Churchill Way, one end of which is at the St Paul’s roundabout, constructed across part of the old gaol grounds.

The demolition of Radnor House in the late 1960s

© Salisbury Newspapers

Even though Fisherton Gaol has long since gone, relics still remain including one of the gaol windows and a prison cell door.

© Frogg Moody collection